The ocean has always been one of Earth’s best defences in the fight against anthropogenic climate change. It absorbs about 25% of the carbon dioxide (CO₂) we emit, acting as a giant sponge for greenhouse gases. This carbon sink comes at a cost—this extra CO2 is making the ocean more acidic, and ocean acidification limits the amount of CO2 the ocean can continue to take in. But what if we could make the ocean even better at this job? Here enters Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement (OAE)—a promising carbon removal method that could help tackle climate change by supercharging the ocean’s natural ability to store CO₂.

OAE is a process that involves adding certain minerals or alkaline substances to seawater to make it more basic (reversing ocean acidification). When seawater is more alkaline, it can hold onto more CO₂ by turning it into stable forms like bicarbonate and carbonate. This means the ocean has space for more CO₂, pulling it out of the atmosphere and helping to reduce the warming effects of CO₂.

What’s more, the materials used in OAE—like ground-up rock (olivine), steelmaking byproducts (slag), or even simple substances like sodium hydroxide—are often cheap and widely available. This method sounds all well and good in theory but, as with any big idea, there are questions we need to answer before we apply this one at a large scale. This is particularly true regarding the effects it may have on the ocean’s biology.

Understanding how OAE affects phytoplankton (tiny floating plant-like organisms) is crucial because these tiny organisms are more than just fish food—they play a massive role in the ocean’s carbon cycle and, by extension, the Earth’s climate system. If OAE benefits some species of phytoplankton but harms others, it could have ripple effects throughout the ecosystem. Some materials, like steel slag or olivine, contain trace metals such as iron and manganese. These are nutrients that phytoplankton need to grow but are typically scarce in seawater. Adding them might give certain species of phytoplankton a boost, but it could also disrupt the balance of the ecosystem.

Testing the waters

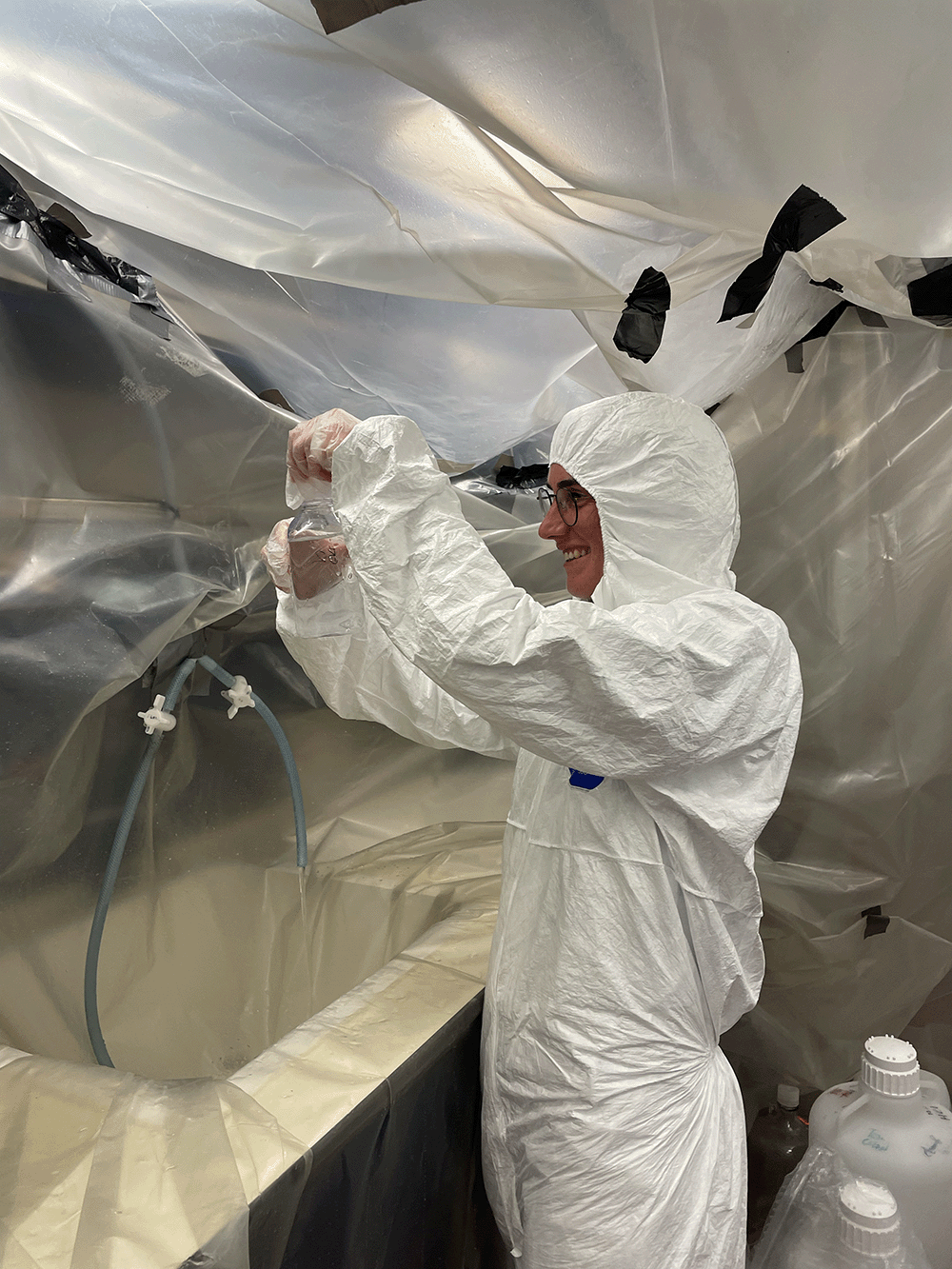

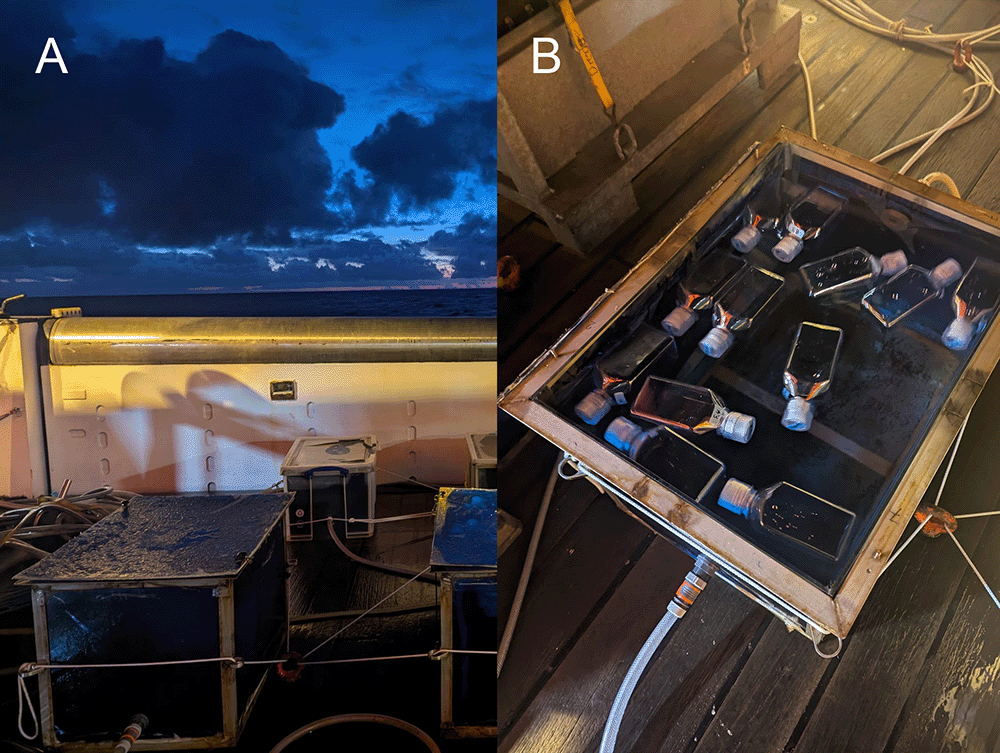

To understand how OAE might affect phytoplankton, we conducted 27 experiments on the back deck of the Sonne in special incubators that mimic natural conditions. We collected trace metal clean water using a device called a Towfish, which “swims” along beside the ship and continually pumps in surface water into a trace metal clean area of the lab called the Bubble.

In the Bubble, we partitioned the seawater into small bottles and added different alkaline materials—like sodium hydroxide, calcium oxide, olivine, and steel slag—to see how they affected the seawater chemistry and phytoplankton, measuring changes over 48 hours.

OAE is still in its early stages, and there’s a lot we don’t know. But one thing is certain: if we’re serious about tackling climate change, we need bold, creative solutions to deal with the existing excess CO₂, even if we find ways to reduce emissions (both processes together are referred to as decarbonisation). By carefully studying the impacts of OAE, we can ensure that it’s not only effective but also safe for the ocean and all of its creatures.

By Anita Butterley, PhD student at the University of Tasmania. Charlotte Eckmann provided edits.