On a summer day in the south Indian Ocean, it can seem like the sunlight supply is endless. But even on the brightest day, most of the ocean stays dark. Only the upper layer of the ocean receives enough light for phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis, a process that uses light energy to convert the inorganic carbon in carbon dioxide into organic carbon.

The realm of measuring light signatures in the ocean is referred to as bio optics or ocean colour data and can tell us a lot about the constituents in the water as well as the health of the ecosystem therein. Anyone who has seen beautiful satellite images of the ocean with swirling green tendrils on a blue backdrop has observed ocean colour data collected by radiometers affixed to satellites. This phenomenon is caused by the green colour of phytoplankton and other algae in the water. Phytoplankton, however, also emit colour as a part of their photosynthetic process.

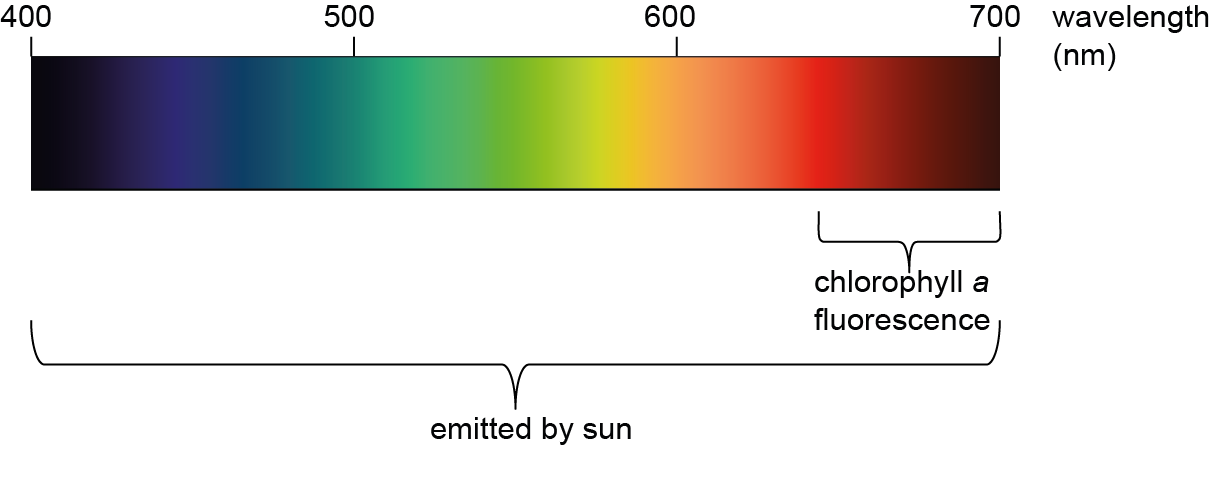

Phytoplankton use pigments called chlorophyll to absorb the light emitted by the sun. However, these chlorophyll molecules also release light, mostly in the red part of the electromagnetic spectrum, as part of this process. This emission of light by chlorophyll molecules—called chlorophyll fluorescence—can vary depending on various factors that can be hard to tease apart. Brandy Robinson, a postdoctoral researcher at GEOMAR, uses measurements of incoming sunlight and outgoing chlorophyll fluorescence to learn more about the factors influencing the photosynthetic process.

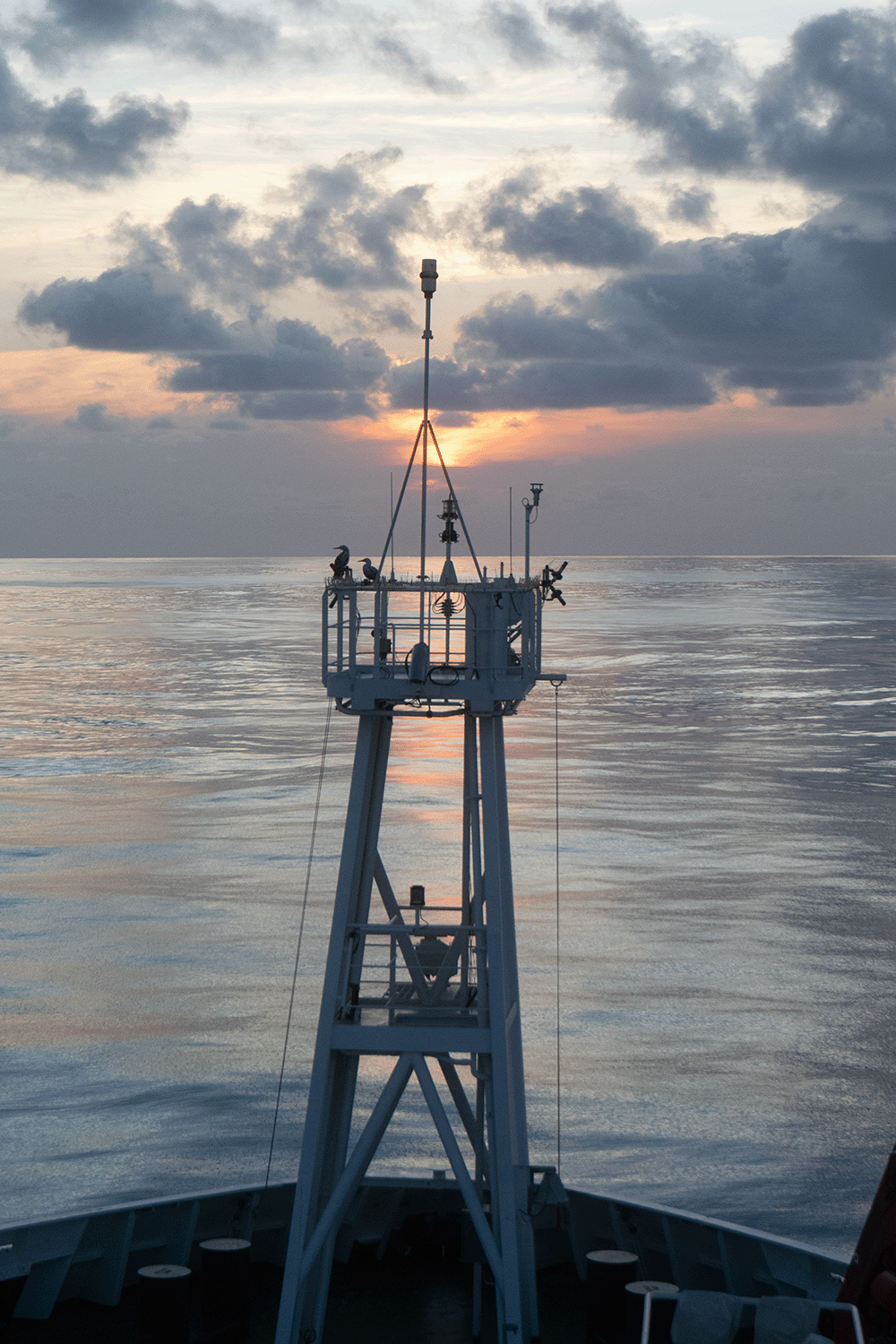

High on the ship’s mast, radiometers perched on the railing of the crow’s nest measure light energy. An irradiance meter measures the total incoming light, while radiometers pointing at the sky and the water surface measure the light being reflected and refracted from these two environments. With all of these various light signatures, Brandy is able to determine the “water leaving radiance”—the light coming from the water itself and from matter within it. The chlorophyll pigments in phytoplankton absorb light in the blue/green part of the spectrum and thus ratio measurements of reflected light in this part of the spectrum are used to determine chlorophyll a and thus phytoplankton biomass. However, fluoresced light from the red part of the spectrum can, in turn, be used to calculate “fluorescence line height” which is far more impacted by changes in the photochemical process. It is this fluorescence signature that she is on the hunt for.

The amount of chlorophyll fluorescence is dependent in part on the amount of phytoplankton in the water and can be used as a proxy for phytoplankton abundance. When trying to determine what other factors influence fluorescence, this impact is corrected for by normalizing fluorescence to phytoplankton biomass. Another factor at play is nutrient limitation. The ‘machinery’ necessary to perform photosynthesis needs various nutrients like nitrogen, iron, and phosphorous to run efficiently. If one or more of these are limiting, the effect can be seen in the fluorescence signature. For instance, under iron limitation, light is collected as usual, but the photosynthetic pathway cannot be completed, leading to more light being released as fluorescence.

Once on land, Brandy will review the radiometer data to see if the fluorescence patterns observed on this cruise follow the predictions based on previous work. However, to understand anything about the fluorescent signature of phytoplankton at sea, it is vital to understand changes in the phytoplankton themselves along the cruise track. This requires collaboration with other scientists on board who will measure biomass, species composition, and nutrient limitation. Thus, during the cruise Brandy is often busy taking fluorometry measurements from incubation experiments (which are the topic of the next post) and assisting with these collaborative efforts—while also maintaining her equipment, which includes periodic check-ups on the radiometers.

The tall ladder to reach the crow’s nest might look unnerving, but to a rock climber like Brandy it’s no big deal—although for safety’s sake she must wait for a calm sea before she can check on her instruments. Anita Butterley, PhD student at the University of Tasmania, is equally undaunted and happy to provide assistance with instrument upkeep.

It’s not always smooth sailing; a shadow was literally thrown over her research when a pair of red-footed boobies decided the mast was a great place to hang out, blocking her sensors. A refortification of the anti-bird-spike defences seems to be holding up so far.

A red-footed booby perches on the radiometer while its companion sits on the railing. Photo by Charlotte Eckmann.

Brandy’s constant vigilance is worth it for the chance to monitor changes in fluorescence across an entire ocean basin and tease apart the photochemical processes occurring in a highly under-sampled area.

By Brandy Robinson and Charlotte Eckmann.