In addition to their CTD duties described in the previous post, Kiel University-GEOMAR Climate Physics masters students Hannah Melzer and Paula Damke are always busy with something, from reading physics books for fun to creating beautiful artwork. Another task under their purview is measuring upper ocean turbulence using a microstructure profiler.

The microstructure profiler is an instrument deployed via a winch at the aft of the ship and allowed to free fall through the water column. Its very sensitive sensors react to the smallest changes in velocity and record those as the probe makes its way downward. As the name already hints, Hannah and Paula use these measurements to document the ‘microstructure’ of the water column, meaning what happens on the microscopic scales over which turbulent mixing occurs.

Turbulence is important for the mixing of properties (such as salinity and temperature) of different fluids—like different layers of water in the ocean. Hannah explained using a caffeinated analogy: if you add milk to coffee and just let it sit, the two fluids will eventually mix due to diffusion, but your coffee will be long cold. But if you introduce turbulence into the system by mixing with a spoon, the points of contact between the milk and coffee are increased, and a homogenous solution—perfectly milky coffee—will be reached while the beverage is still nice and hot.

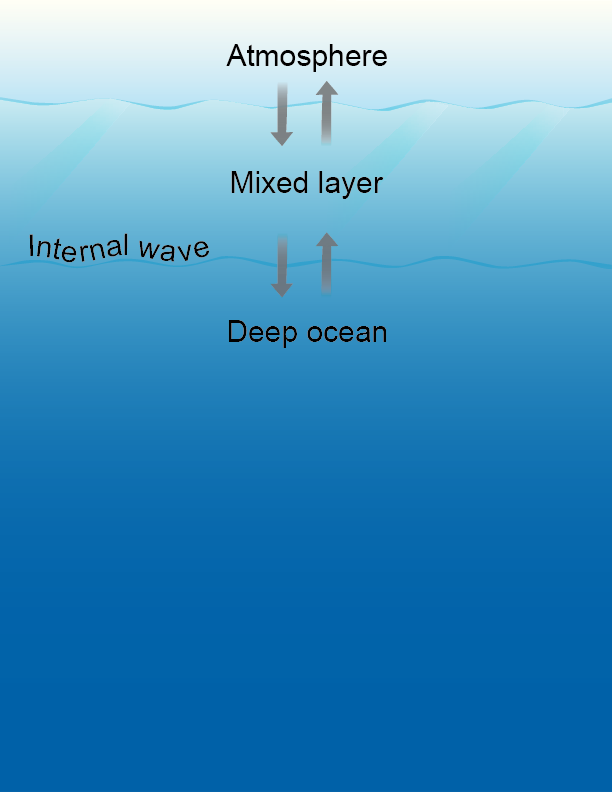

The turbulent mixing between fluids with different densities is often the result of waves along the interface, called internal waves. Only the very top layer of the ocean is in contact with the atmosphere, and there is usually a clear boundary between this upper layer—called the mixed layer since wind influence keeps it well-mixed— and the rest of the water column. This boundary usually prevents mixing between these layers, but internal waves at the bottom of the mixed layer can move trace elements and nutrients from the mixed layer to the deeper ocean and vice versa. Measuring both the strength of turbulence and the concentrations of chemical species (determined from seawater collected via the CTD rosette) throughout the mixed layer and deeper water can provide an estimate of the amount of internal-wave-facilitated exchange.

When people hear the word “turbulence”, they might think of being jostled around in an airplane, but to physicists like Hannah and Paula, it is an important phenomenon for ocean mixing.

By Charlotte Eckmann based on interviews with Hannah Melzer and Paula Damke. Hannah Melzer provided edits.