Carbon’s journey to the deep

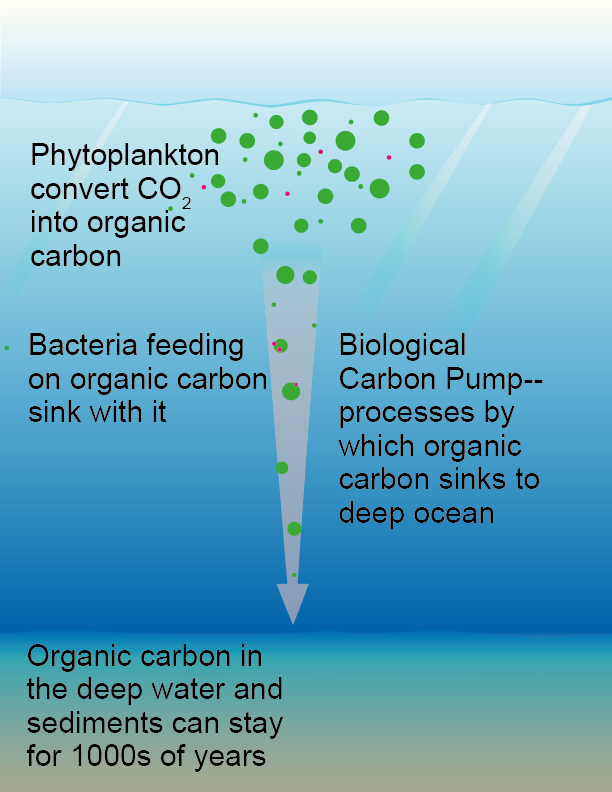

Just like their larger cousins, the terrestrial plants, phytoplankton convert atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) into organic carbon. If their tiny carbon-based bodies sink from the surface ocean to the deep sea and sediments, the CO2 is then removed from the atmosphere for hundreds to thousands of years. The remains of phytoplankton and other detritus sinking through the water column are called marine snow, as they look like falling snowflakes. The processes by which marine snow sinks from the surface to be sequestered in the deep are collectively called the biological carbon pump (BCP), and how well the pump works depends on the types of phytoplankton and the complex web of biological interactions they are a part of.

The sinking phytoplankton remains are a hotbed for hungry bacteria. Thus, by virtue of hitching a ride, bacteria also contribute to the BCP. Since many of the carbon building blocks that make up bacteria are particularly resistant to being converted into CO2, their contribution to the BCP is an important aspect of long-term oceanic carbon sequestration.

How efficient is the BCP across the Indian Ocean transect? And how much do bacteria contribute to the BCP’s sinking carbon? To answer these questions, Wan Zhang and Jinqiang Guo (scientists from GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research) will make good use of the thousands of liters of water that pass through the in-situ pumps introduced in the previous post. But unlike radium-hunting Cátia, they are after sinking bacteria-covered phytoplankton particles.

The case of the missing thorium

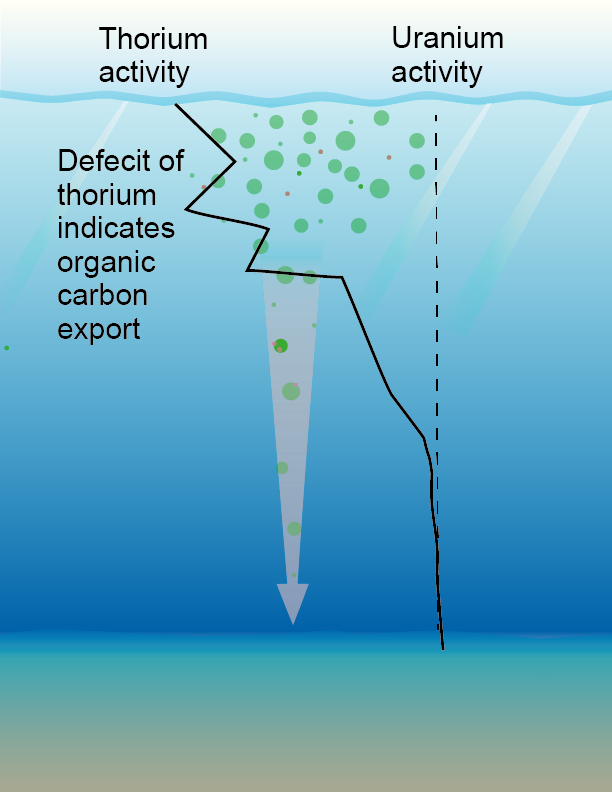

Wan will use thorium isotopes to measure the rate of particle sinking (aka export flux). Like radium, thorium is part of a radioactive decay system used to answer oceanographic questions. Uranium-238 is a naturally occurring isotope in seawater. It doesn’t react much with anything, so it has fairly constant activity throughout the depths of a water column. It decays into thorium-234, and, in an ocean system with no BCP or other biological activity, the ratio of activities of uranium-238 to thorium-234 is constant. However, unlike its parent isotope, thorium is attracted to particles; when a thorium isotope hitches a ride on a sinking particle, it is removed to a deeper depth. Therefore, at the surface, there will be a deficit of thorium-234 to uranium-238, and the amount of that deficit correlates to the strength of the BCP at that location.

Wan will use an instrument called a beta counter to measure thorium activity in the particles collected by the pumps. The beta counter was down for the count for a few weeks, but thanks to the tireless efforts of André Mutzberg (GEOMAR), it is now in working order. Once she measures the activities, Wan can then use the activity ratios of uranium-238 and thorium-234 to estimate the export flux of the BCP.

Bacterial forensics

Meanwhile, Jinqiang is searching the particles collected by the pumps for signs of bacterial origin—a bit like a detective trying to match fingerprints at a crime scene. One “fingerprint” he’s on the lookout for is muramic acid, which is a component of the cell wall in bacteria. Since phytoplankton don’t use this particular carbon building block, it’s a good choice of bacterial biomarker. He will use the amount of muramic acid and other biomarkers as a proxy for how much bacteria is in the particles of the BCP. Combined with Wan’s BPC flux estimations, this can tell us how important bacterial carbon is to the BPC and if that is tied to the strength of the BCP.

Adding it all together

It’s important to know both the strength of the BCP and the types of organic matter that contribute to it so that we get a better understanding of how much carbon is shuttled to the deep sea and how likely it is to stay there. The ability to sequester carbon from the atmosphere can mitigate the excess of CO2 released into the atmosphere from human activities.

Written by Charlotte Eckmann based on information provided by Wan Zhang and Jinqiang Guo.