As I mentioned in my previous post, every scientist has a different opinion on what success looks like for marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR). Some believe that the risks are worth the benefit because the risks of unmitigated climate change are far higher than the risks associated with mCDR. At the other end of the spectrum, some people are interested in mCDR as a concept but are sceptical of whether it should actually be applied. Others in the middle believe that we can’t control whether mCDR will be implemented, but we can at least provide information to help make sure that sensible decisions are made.

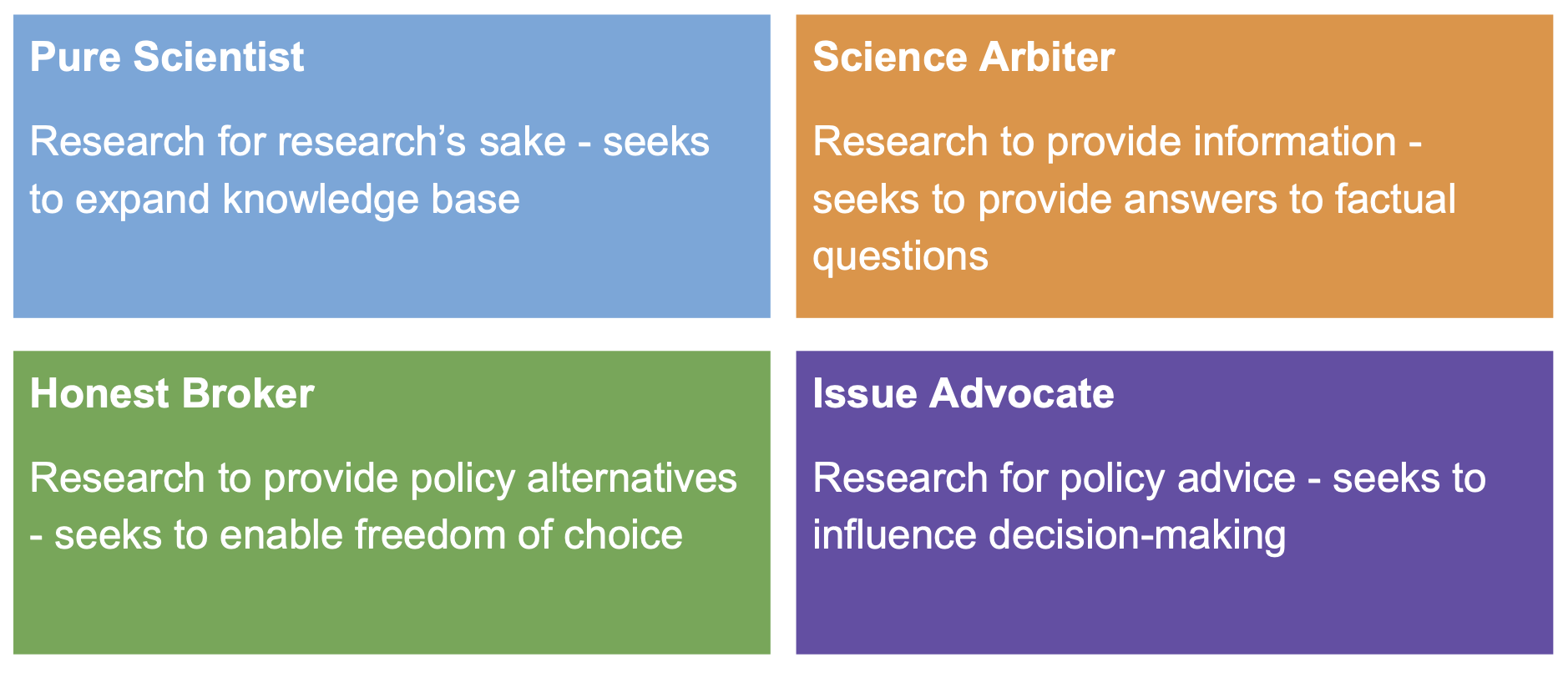

But whatever an mCDR researcher’s opinion on how or whether mCDR is implemented, the fact is that they have chosen, for whatever reason, to research it. So we have to make a decision about how to communicate our science. Do we have the responsibility to be unbiased, and present information to let relevant decision-makers decide and do what they want? Or do we have the responsibility to use our position as an expert to provide guidance? In his 2007 book ‘The Honest Broker’, Roger Pielke outlined 4 different archetypes of scientific communicator, which you can see in the sketch below.

We are all capable of embodying all of them at different points in our careers and as we speak to different people. The aim of the workshop session I co-led in February at the National Oceanography Centre’s Socio-Oceanography Workshop was to examine the dynamic nature of these roles and how they change in different contexts.

The workshop is built so that each session is led by a natural and a social scientist, and natural and social scientists alike are encouraged to attend. This opened the workshop up to some fantastic interdisciplinary methods and conversation, which was perfect for addressing our question about the communication of mCDR research. Together with my social science co-lead (Javier Mármol Queraltó at Southampton University), we created representative scientist personas to use as devices for role-play in hypothetical scenarios relating to mCDR research. These included communication with members of the public, policy and decision-makers, and other members of academia. This sounds a bit awkward as a concept, especially since we were mainly mCDR researchers in the room anyway, so why should we need to use fake people?

But the advantage is that it takes the ego out of the conversation and allows for more creativity: when we’re not bound by our own contexts and opinions, there’s so much more space to think about what could happen. We split into groups to do this, and every group had their unique way of addressing the exercise which led to our personas embodying a truly dynamic, relational and subjective set of archetypes. Depending on which personas each group put in each context, how they interacted, and how each group interpreted the description of the context and the personas, we found a different outlook on the communicative roles the personas took on, and how appropriate this was for the persona and the context! I had a great time facilitating the insightful discussions that came out of these exercises, and my session co-lead and I are both really grateful that the socio-oceanography workshop exists to support such a collaborative, creative and interdisciplinary group of people – please check out the summary of all the sessions to find out more about what happened this year!

Sandy