English version below

Heute begleiten wir Julia vom Institut für Chemie und Biologie des Meeres der Uni Oldenburg bei ihrer Arbeit auf der Maria S. Merian. Im letzten Beitrag ging es schon ein bisschen um die Unterwegsdaten, die auf Schiffen gemessen werden. Julia hat noch ein weiteres Gerät mitgebracht, das auch in diese Kategorie fällt: eine FerryBox.

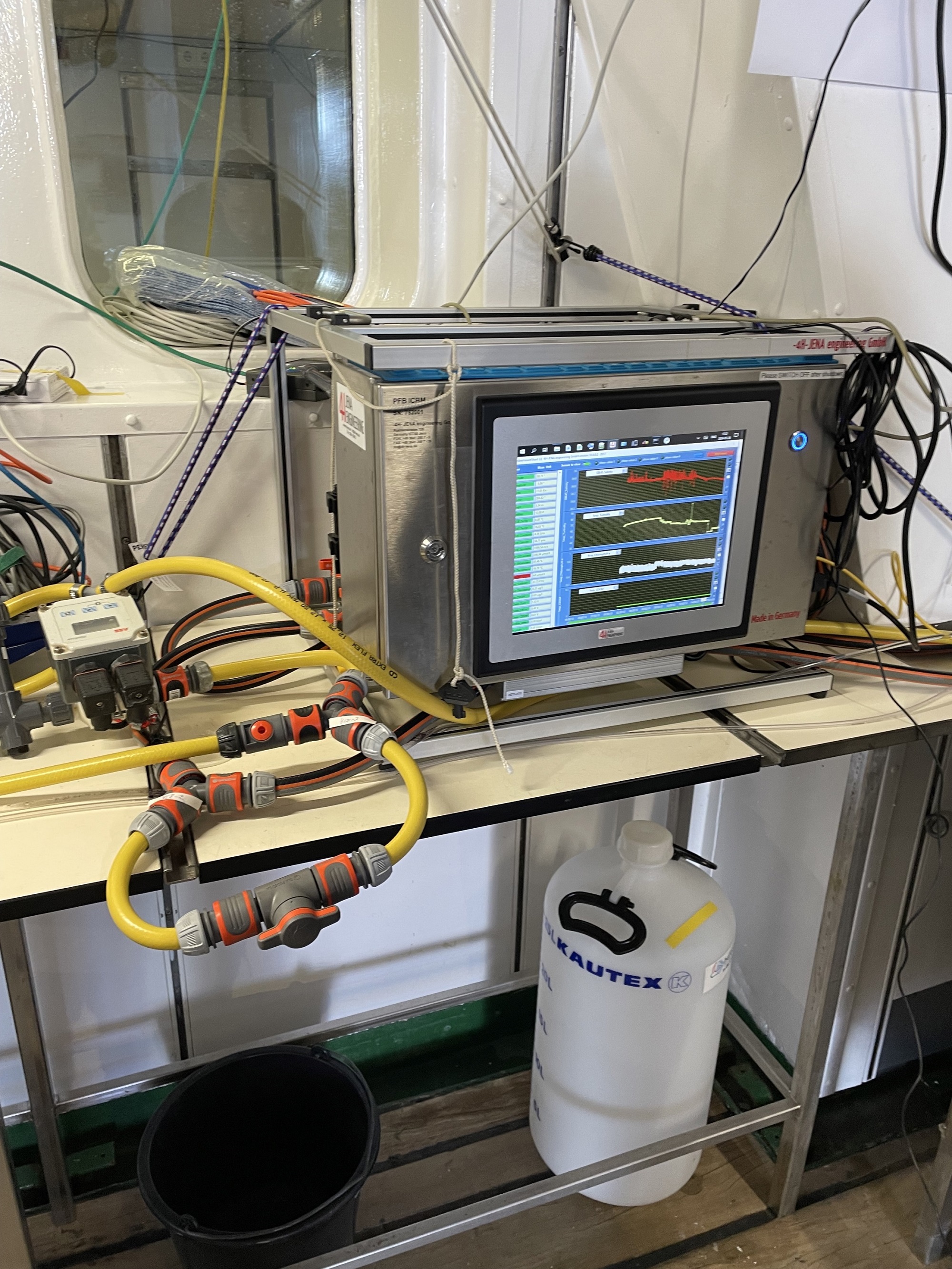

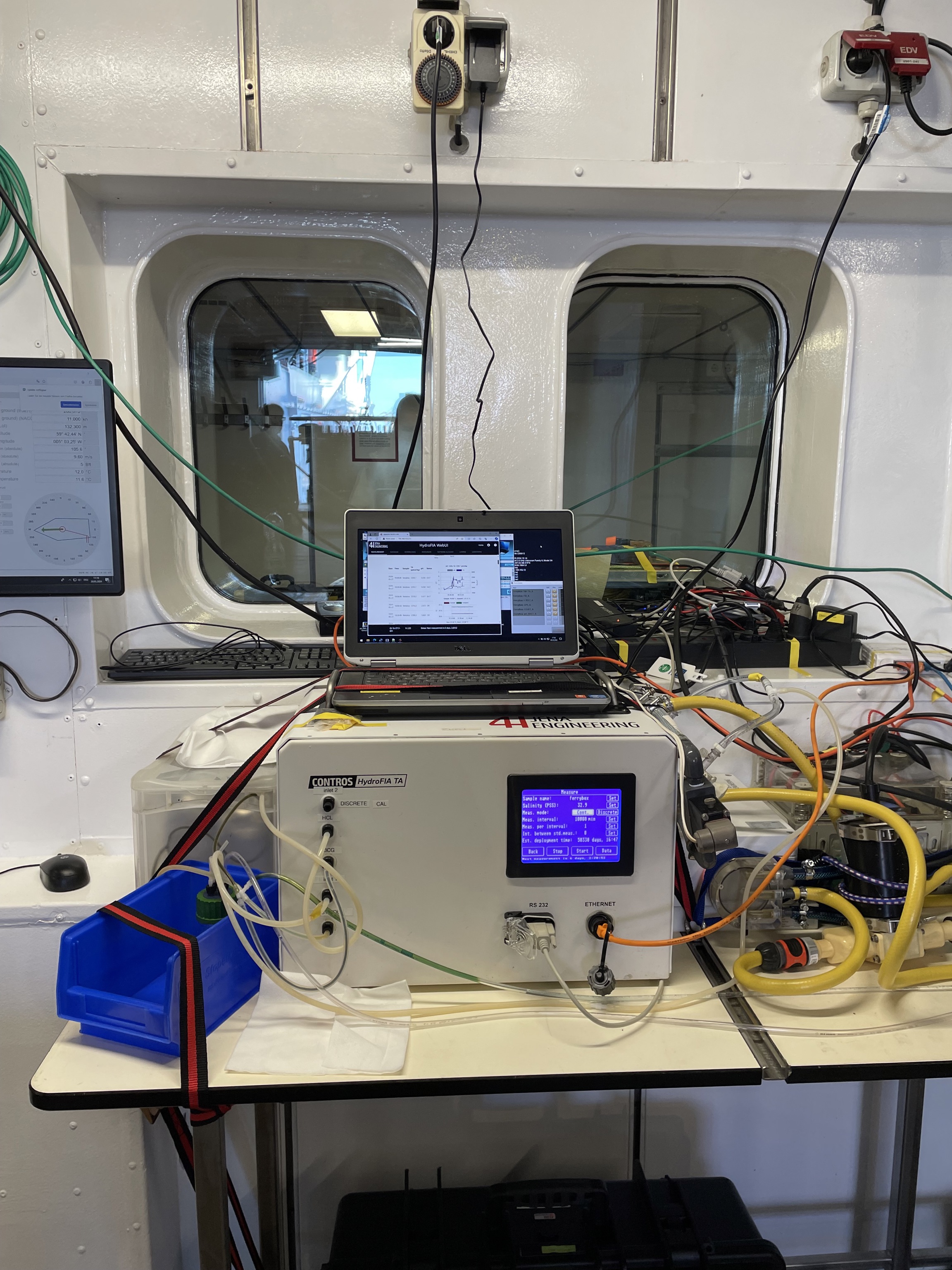

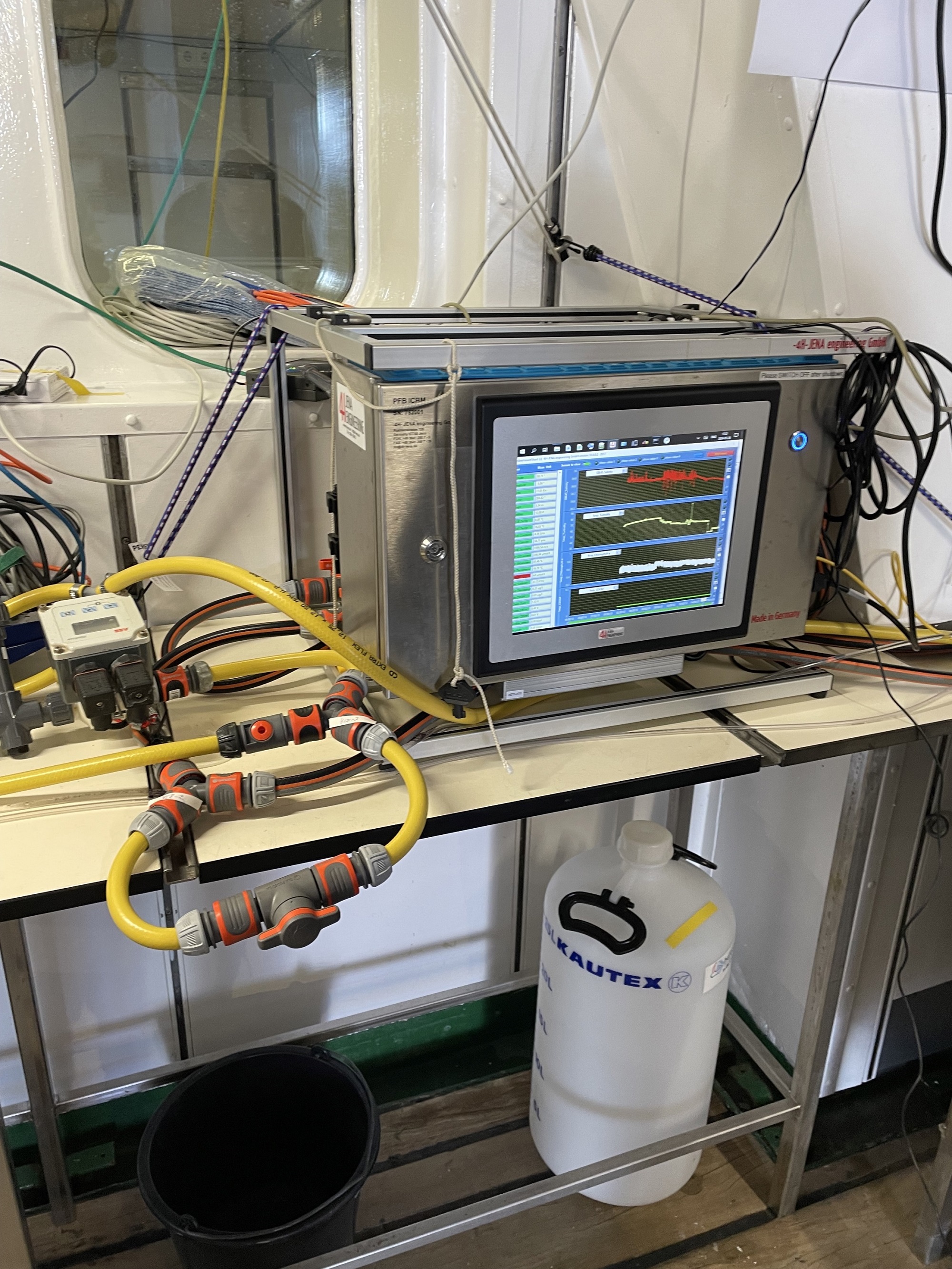

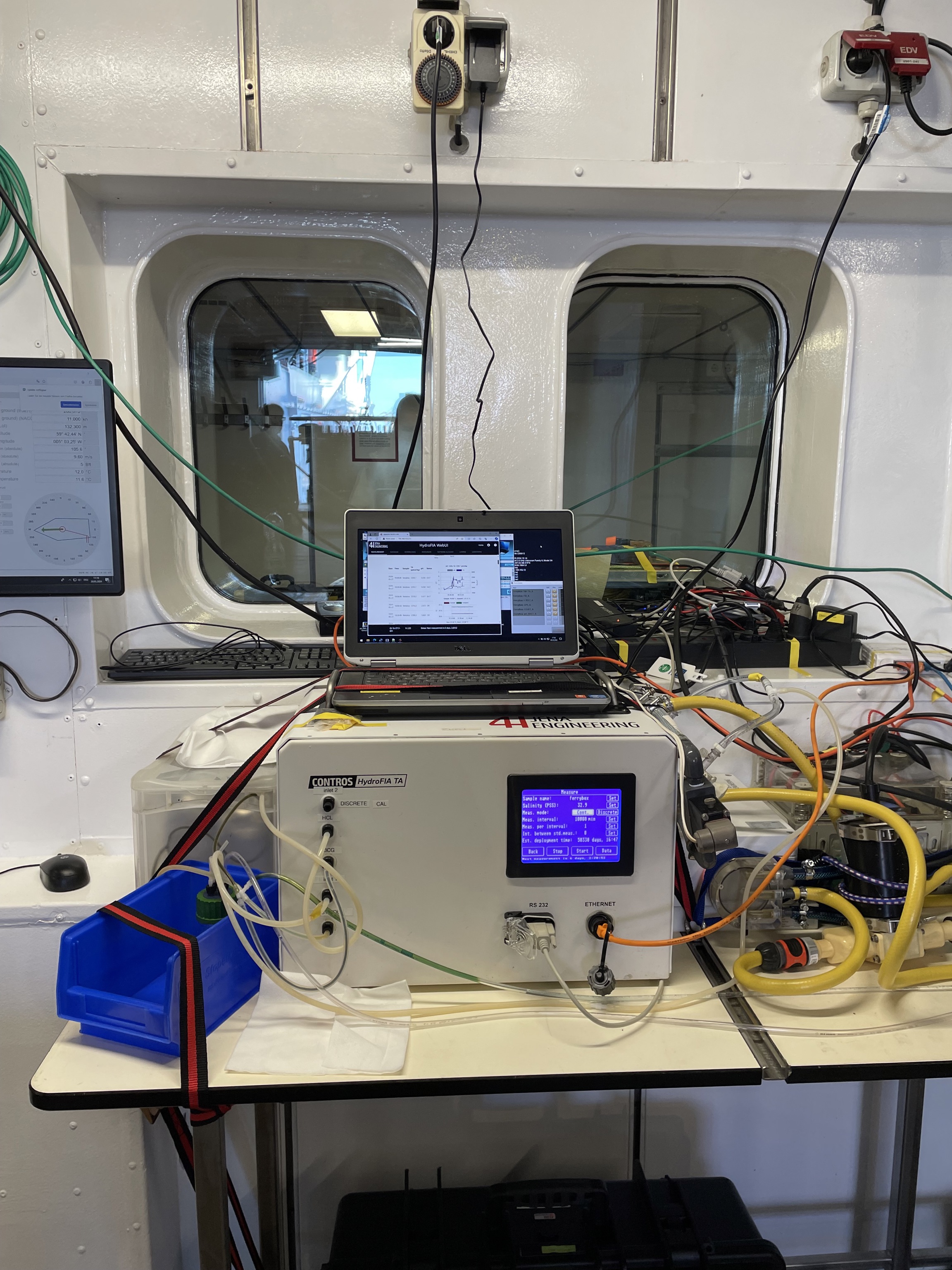

Die FerryBox ist ein sogenanntes Durchflussgerät. Das bedeutet, dass Wasser unter dem Schiff mit einer Pumpe angesaugt und durch das Gerät geleitet wird. Dann kann das Messgerät Temperatur und Salzgehalt des Wassers messen. Diese beiden Größen sind wichtig, da sie die Dichte des Wassers bestimmen und damit Aufschluss über Strömungen geben. Außerdem misst das Gerät auch bio-optische Werte, nämlich Chlorophyll A und CDOM (Colored Dissolved Organic Matter = farbige gelöste organische Substanz auch Gelbstoff genannt). Chlorophyll gibt Aufschluss darüber, wieviel Phytoplankton sich im Wasser befindet. Phytoplankton sind kleine Algen, die die Grundlage für das gesamte Nahrungsnetz des Meeres bilden. Der große Vorteil der Ferry Box ist ihr modularer Aufbau. So können zum Beispiel auch Sensoren für totale Alkalinität (wieviel Säure das Wasser binden kann), Kohlenstoffdioxid oder PH-Wert zusätzlich angebaut werden.

Das sind also alles wichtige Größen, um Prozesse im Meer zu verstehen. Aber warum ist das Gerät genau an Bord und woher kommt der Name FerryBox?

Vielleicht fangen wir mit der Namenserklärung an. Die FerryBox ist dafür gedacht auf Fähren (englisch: ferry) mitzufahren. Fähren bieten sich gut dafür an Messgeräte mitzunehmen, da sie regelmäßig die gleiche Strecke fahren. Die Ferry Box ist ein kastenförmiges Gerät, dass autonom messen kann und nur von Zeit zu Zeit von einem Wissenschaftler oder einer Wissenschaftlerin gewartet werden muss.

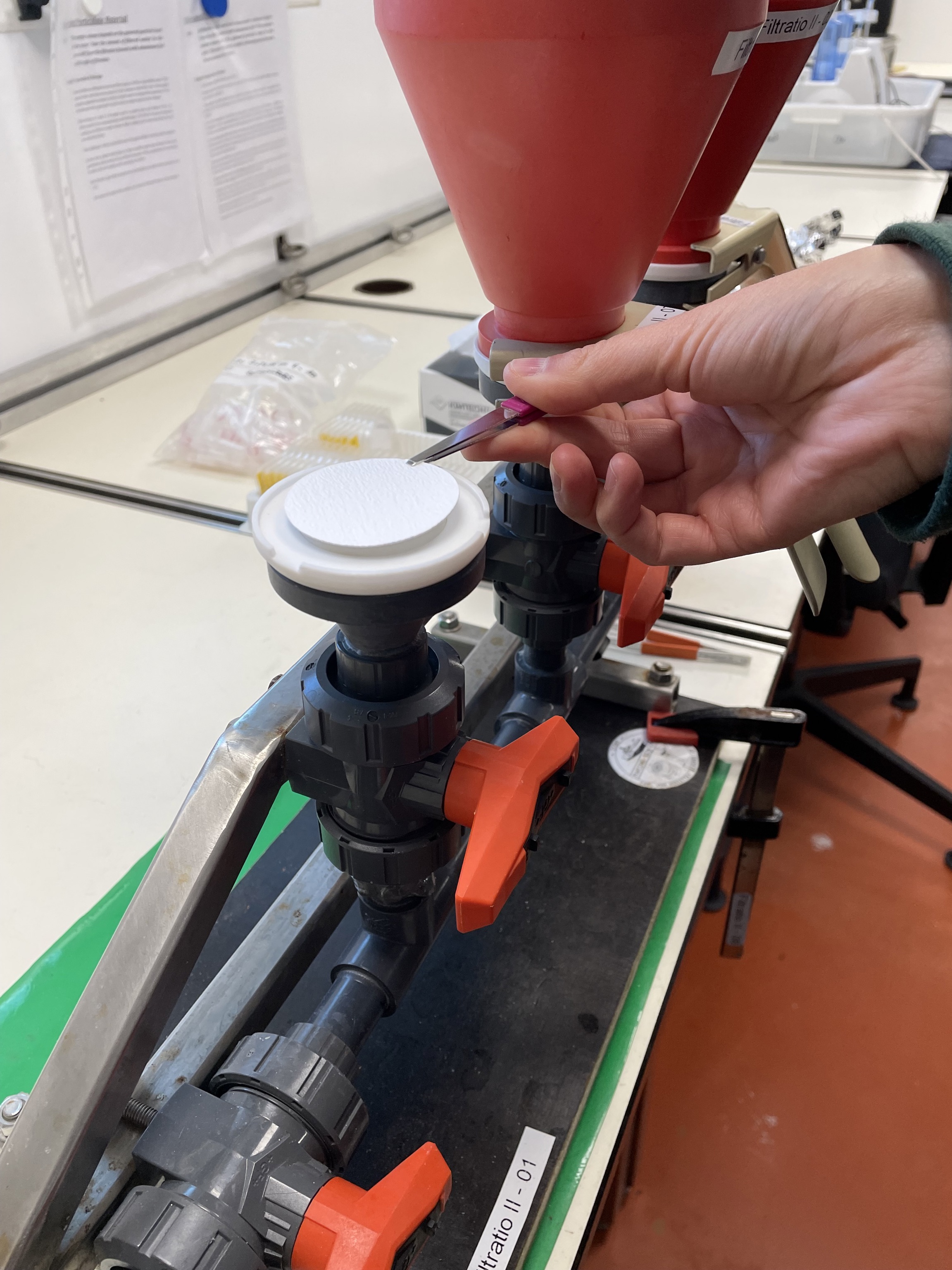

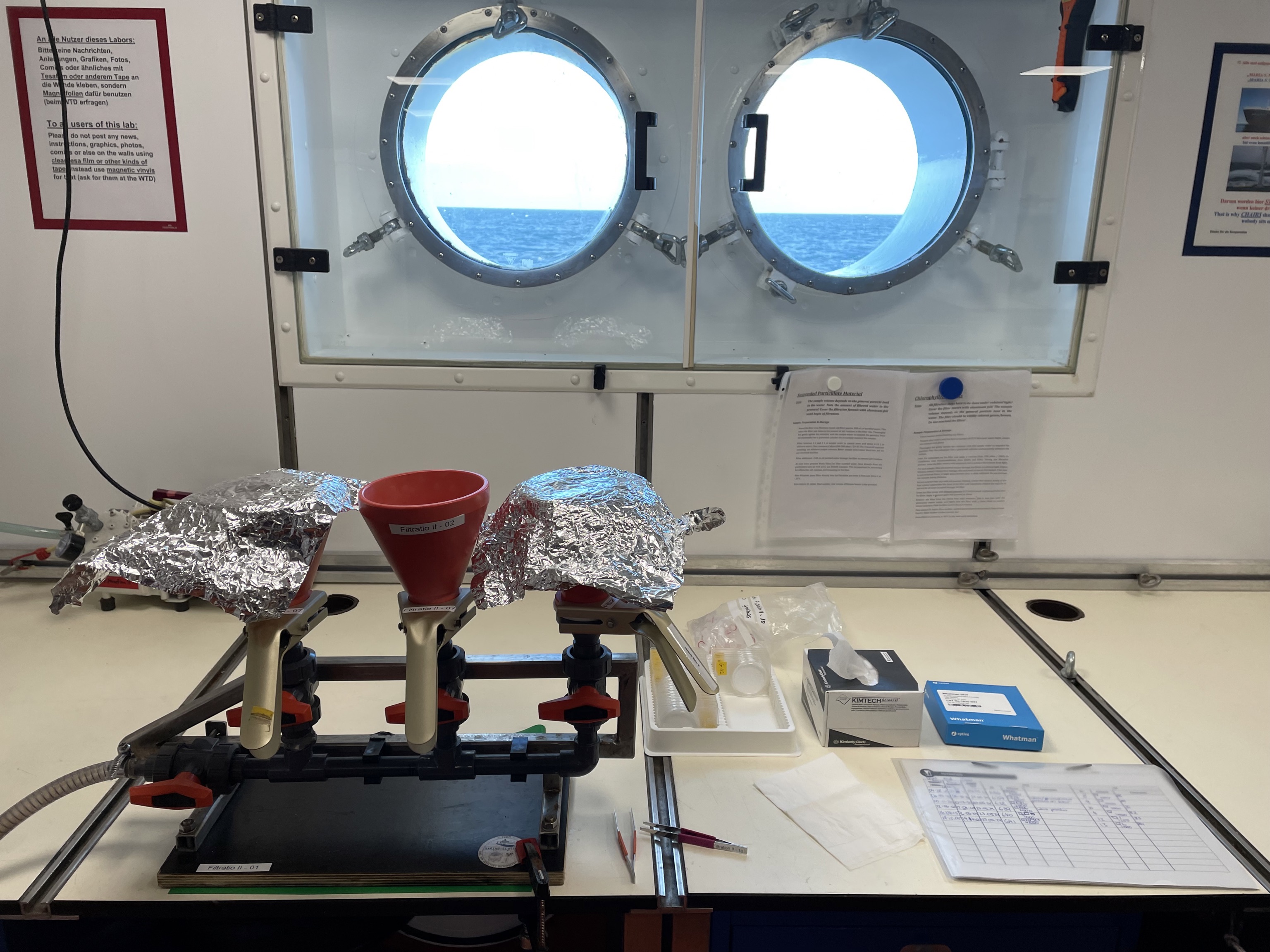

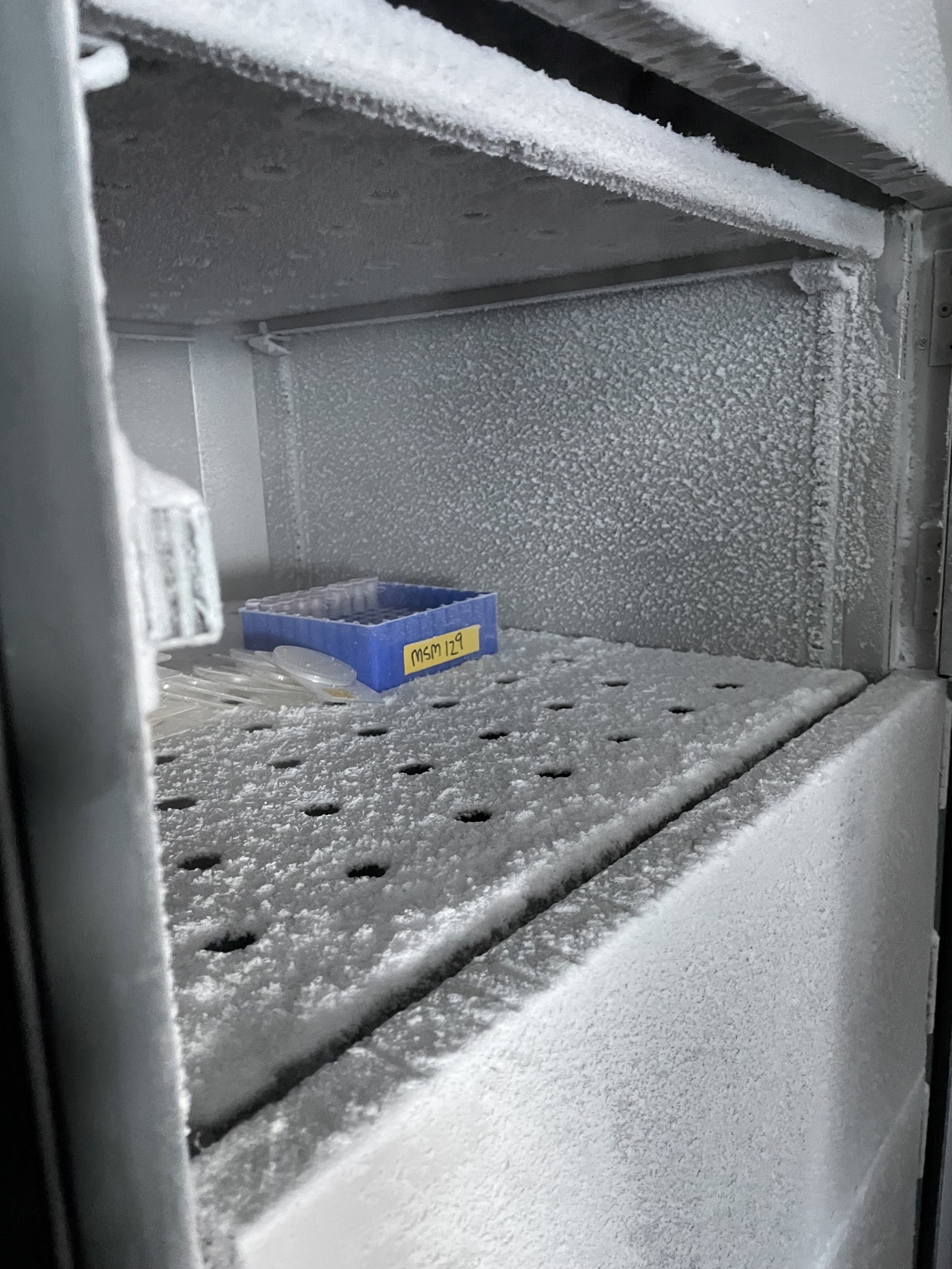

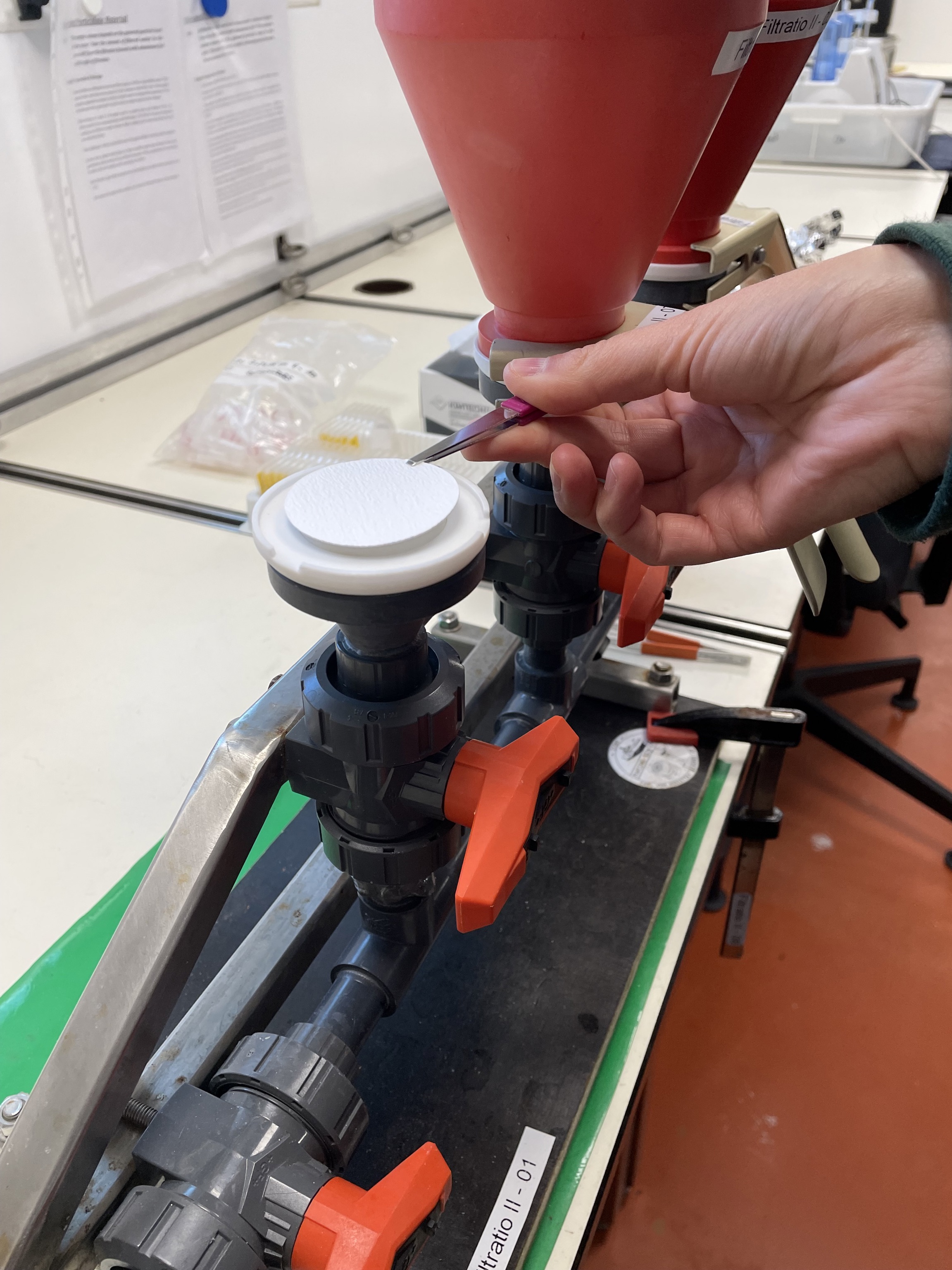

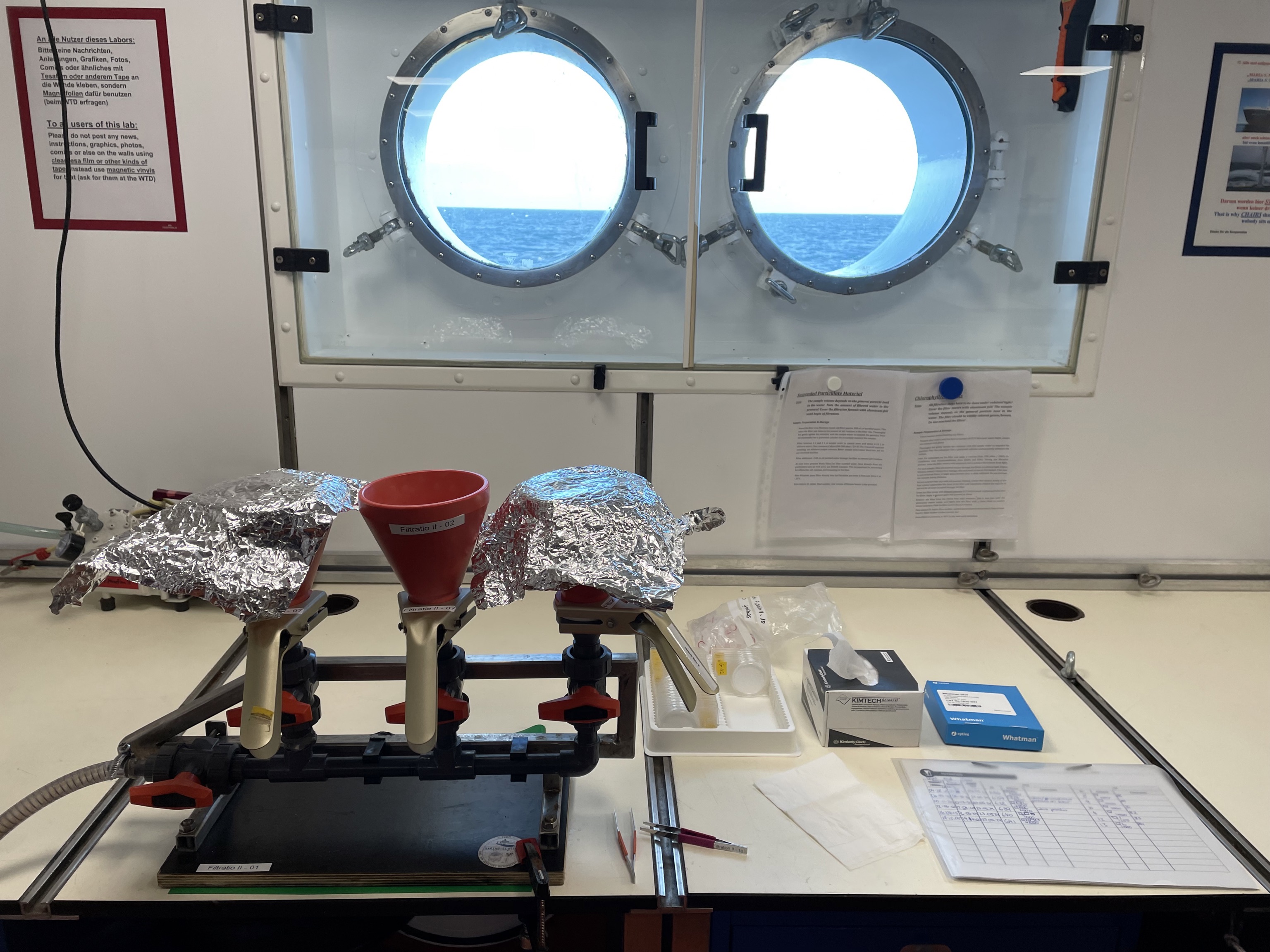

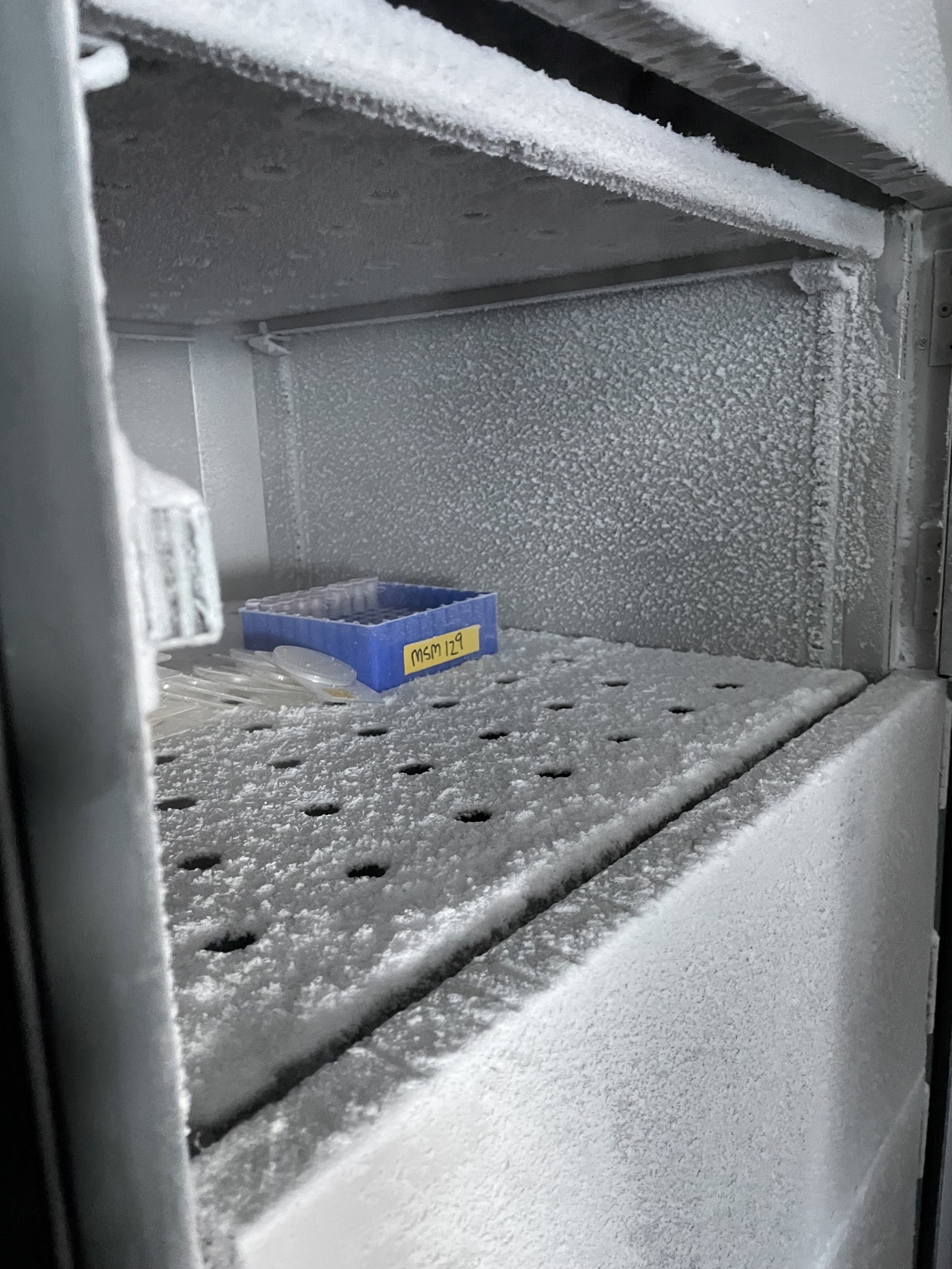

Das große Ziel dieses ersten Teils der Forschungsfahrt ist es, die Übertragung der Daten von Messgeräten an Land zu optimieren. Die FerryBox kann beispielhaft dafür betrachtet werden. Julia hat sie an Bord gebracht und kümmert sich jetzt zusammen mit Norbert vom Alfred-Wegener-Institut darum, dass die Daten annähernd in Echtzeit an Land übertragen werden. Wenn sie im zweiten Teil der Forschungsreise wieder an Land in ihrem Büro ist, kann sie die Daten an ihrem Computer abrufen. Sollte dann ein Fehler auftreten, kann sie direkt auf dem Schiff Bescheid sagen, damit das Problem direkt behoben werden kann. Zusätzlich dazu kalibriert Julia die FerryBox auch noch. Dafür lässt sie Wasserproben im Labor durch einen Filter laufen und lagert sie danach in einem Kühlschrank, der eine Temperatur von -80°C hat. So bleiben die Proben haltbar, bis sie im Anschluss in Deutschland in einem Labor ausgewertet werden.

Am Ende soll die entwickelte Software als Blaupause für anderen Geräte nutzbar sein. Die annähernden Echtzeitdaten sind dann auch öffentlich sichtbar und können von jedem genutzt werden.

The FerryBox

Today we accompany Julia from the Institute of Marine Chemistry and Biology of the University of Oldenburg in her work on the Maria S. Merian. The last post was a bit about the underway data, which are measured on ships. Julia brought with her another device that also falls into this category: a FerryBox.

ph-value (Photo: Christiane Lösel)

The FerryBox is a so-called flow device. This means that water under the ship is sucked in with a pump and passed through the device. The instrument can then measure the temperature and salinity of the water. These two quantities are important because they determine the density of the water and thus provide information about currents. In addition, the device also measures bio-optical values, namely chlorophyll A and CDOM (Colored Dissolved Organic Matter). Chlorophyll provides information about how much phytoplankton is present in the water. Phytoplankton are small algae that form the basis of the entire marine food web. The great advantage of the Ferry Box is its modular structure. For example, sensors for total alkalinity (how much acid the water can bind), carbon dioxide or PH value can also be added.

So these are all important variables for understanding processes in the ocean. But why is the device on board and where does the name FerryBox come from?

Maybe we’ll start with the declaration of names. The FerryBox is meant to be used on ferries. Ferries are good for carrying measuring instruments, as they regularly travel the same distance. The FerryBox is a box-shaped device that can measure autonomously and only needs to be maintained by a scientist from time to time.

The main objective of this first part of the research trip is to optimise the transmission of data from measuring instruments to land. The FerryBox can be seen as an example of this. Julia brought them aboard and, together with Norbert from the Alfred Wegener Institute, is now making sure that the data is transmitted to shore in near real time. When she is back ashore in her office during the second part of the research trip, she can retrieve the data from her computer. If an error should occur, she can notify the ship directly so that the problem can be rectified immediately. Julia also calibrates the FerryBox. To do this, she passes water samples through a filter in the lab and then stores them in a refrigerator with a temperature of -80°C. This means that the samples remain stable until they are subsequently evaluated in a laboratory in Germany.

In the end, the developed software should be usable as a blueprint for other devices. The near real-time data is then also publicly visible and can be used by anyone.