Pozdrav iz Pule!

Meet Barbara and Catarina, two students to whom the Meeresschule (Marine School) in Pula is their home since April. Barbara (24) from Croatia is studying experimental biology, module physiology and immunobiology at The Faculty of Science in Zagreb. She is interested in implementing human health in the field of sustainable development, but also in marine biology and the latter was her motivation to become a GAME participant. Catarina (27) is from Portugal, she grew up by the ocean and has always been mesmerised by marine life. She is studying in the Master programme “Sustainability, Society and the Environment” at Kiel University and she was eager to immerse herself in this captivating study and to contribute to the advancement of scientific knowledge in this field.

The ancient city of Pula is located on the coast of the Adriatic Sea in Croatia, where history and natural splendour are visited by many tourists during summer. The Marine School is a marine biology centre that has developed into an educational and researc institution, which is recognized throughout Europe, since its foundation in 2000. While living here, we have met many volunteers who are working for the Marine School, an who are mostly biology students from Austria and Germany. Their work is to give courses for pupils from Germany and Austria and they are passionate about their field of studies. Furthermore, they not only share their theoretical knowledge about marine ecosystems with the pupils who visit the Marine School, but also place great emphasis on teaching them practical skills that enable them to work safely near and in the sea.

This year the GAME teams focus their research on the question how artificial light at night (or ALAN as we like to call it) affects macroalgae’s photosynthesis, their capacity for primary production as well as their tissue toughness and colour (which are indicators for their health).

We started our practical work in spring and April and May were intense months forus as numerous decisions had to be taken that were related to the implementation of the experimental set-up. This had been developed by the entire group of GAME students at GEOMAR in Kiel back in March. We also needed to find answers to key questions such as:

Which algae species to use? Which grazer species? Where and how to collect these organisms? How do we set-up everything in the laboratory? Which materials do we need to order/buy? How long will it take for the materials to arrive? How do we build a penetrometer? (A penetrometer is a simple mechanical device that allows to assess tissue toughness in plants. It is basically a blunt needle that is pushed into the algal thallus, while the force is measured that was needed to penetrate into the tissue.) To answer all questions listed above, we really had to use our creative and organisational skills, while, at the same time, we needed to be a mix of builders, electricians, explorers, and researchers.

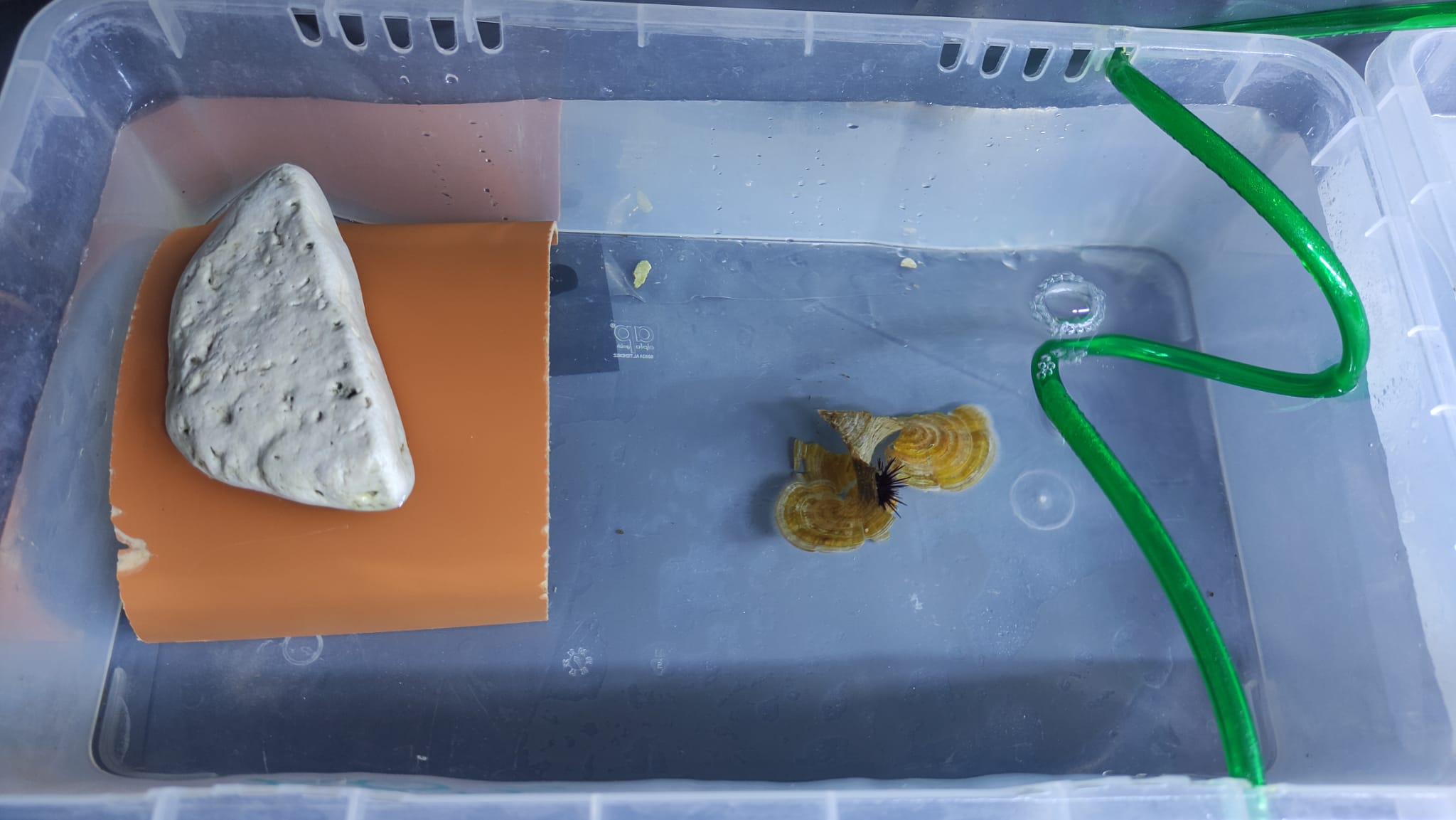

Initially, we had planned to use grazers such as snails or sea urchins in our experiments in order to induce a chemical defence against grazing in the macroalgae. This is a common reaction in seaweeds when they are attacked by herbivores and it is based on secondary metabolites that make the alga unattractive for their enemies. The induction of such a chemical reaction would have allowed us to test whether ALAN can impair the capacity of macroalgae to defend themselves against grazing. To prepare this, we started our first pilot study to determine the consumption rate of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus on the brown alga Padina pavonica by the end of May. This was done to assess for how long we could keep the sea urchins in contact with the algae without losing all the algal tissue due to grazing. However, we observed that the sea urchins consumed a significant amount of the algal material in a very short time and this made our original experimental design challenging to implement. This was because the algae that we found in the waters near the Meeresschule were rather small sized. Hence, it was clear that they would not survive for long in the presence of grazers. Therefore, no algae would have been left by the end of our experiment, even in case the sea urchins were only in contact with the algae for a few days. Therefore, we decided to exclude the grazers from our experimental design, what also meant that we could not test whether ALAN has an effect on algal defences.

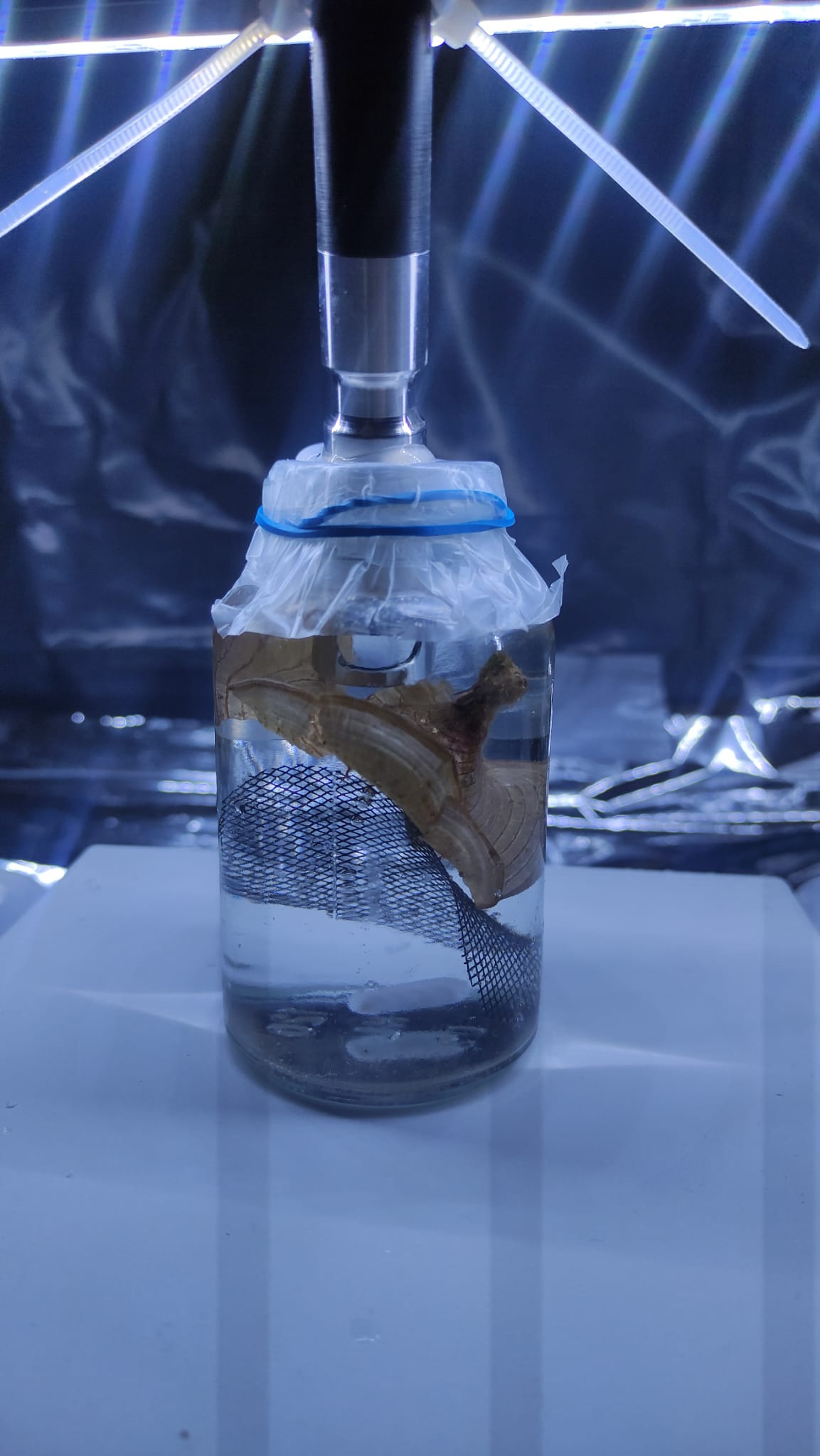

Just as we were about to begin the second pilot study, our oxygen sensor broke (it was pretty old, probably tired of working and just wanted to retire) and this delayed the start of the main experiments. However, with the help from the Pula Aquarium and from this years’ wonderful Team Wales, who shipped us their sensor from Bangor, we managed to conduct the second pilot study by the end of June. Since we were running out of time, we powered through this by working nonstop in the lab for manyyyy hours. Even though both of us had never done any oxygen evolution measurements with macroalgae on beforehand, this pilot study was very successful, and we were able to develop method to obtain data about the oxygen production and by this about the photosyntheti performance of the algae that also worked very well in the main experiment.

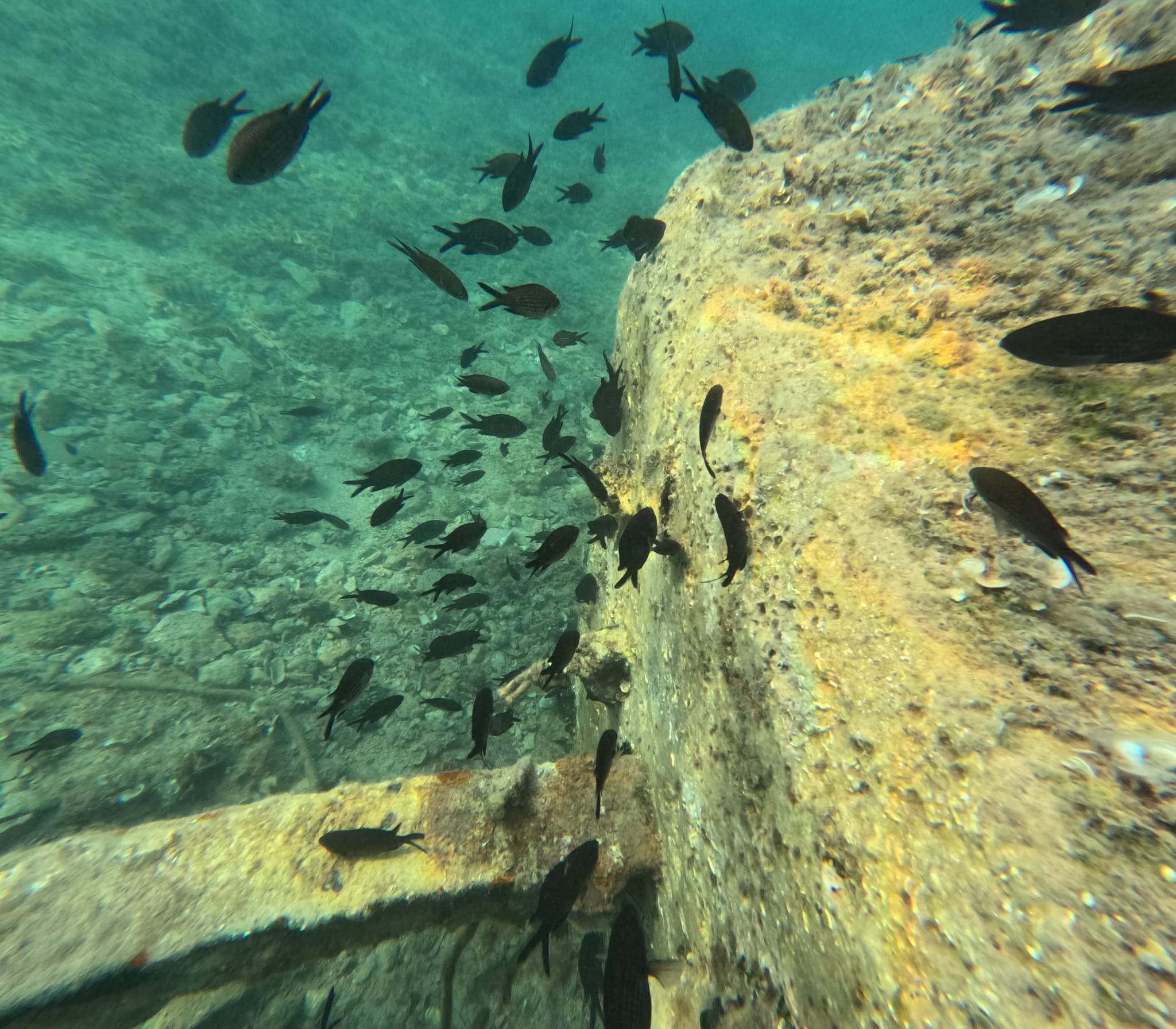

Another problem that we were facing since the start of our work was the lack of an abundant algae species on site. This even got worse as we went through the summer months, most likely due to the air and sea surface temperatures that were particularly high this year, reaching 32°C-36°C in air during the day and 22°C-29°C during the night. The sea surface temperature was around 11°C in April and reached almost 28°C by the end of August! This massive increase could have been a disturbance for the shallow-water eco-systems of the Adriatic Sea. Nevertheless, after countless snorkelling trips through most of the bays in Pula, we wer lucky enough to find enough P. pavonica individuals for our experiments.

In the first week of July, we finally started our first main experiment on the effects of ALAN on P. pavonica. This was successfully finished after 21 days, and we then immediately started our second main experiment which was over by the mid of August. The main difference between the two experiments was the intensity of the applied light at night. Since we did not find an effect with an intensity of 30 lux in the first experiment, we went for a higher intensity in the second experiment. Until the end of September, we are planning to accomplish a third experiment – given that we will find enough algal individuals for it! Furthermore, we were conducting an extra pilot study to find out, if ALAN has any direct effect on the photosynthetic performance of P. pavonica.

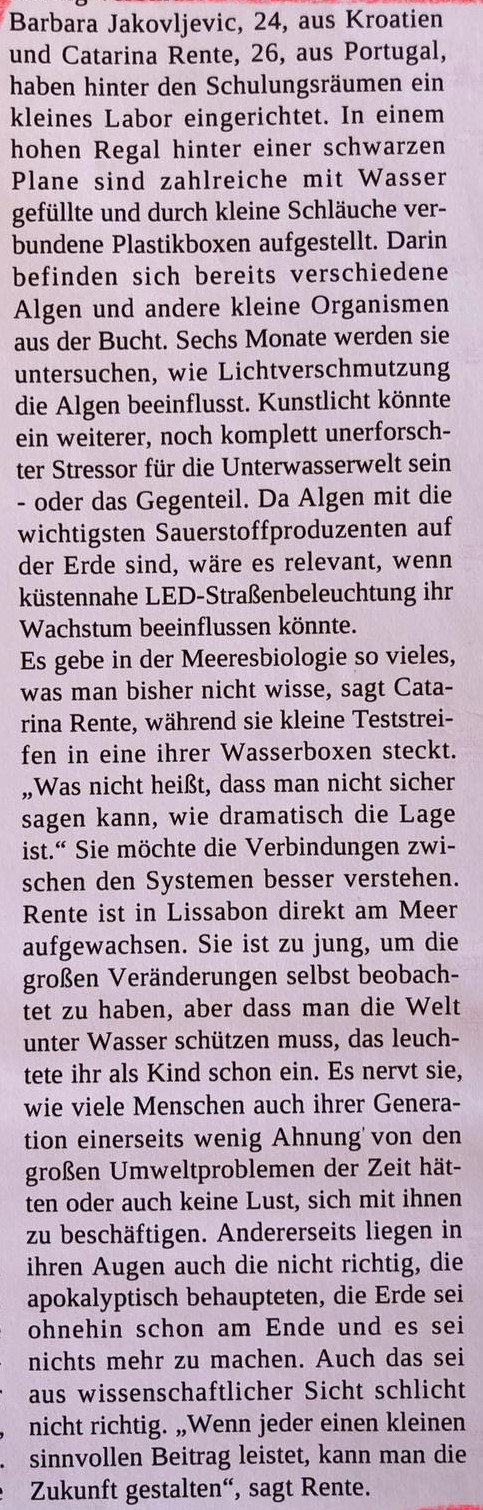

In the last two months, we also had the pleasure to be interviewed by the Süddeutsche Zeitung, Deutsche Welle, and by the Croatian national TV HRT, who were all interested in our research in Pula.

In our free time, besides visiting the 2000 year-old Colosseum in the city center of Pula, we have been to a few music concerts, as well as to Cape Kamenjak, which is a nature reserve where limestone cliffs plunge into the blue sea. When snorkelling in Pula, it is possible to observe many different species of fish, starfish, crabs, sea cucumbers, sea urchins, jellyfish, and we even spotted a seahorse once!

Furthermore, when we are not in the lab, we enjoy spending time together with the volunteers at the Meeresschule, going on snorkelling trips, enjoying the sun and the mesmerising sunsets, or simply cooking a meal together and talking through the night.